Mon 12 January 2026

Seating Charts

We have two large tables and 100 guests coming to our wedding and we have to figure out how they will be seated. Defining the seating chart tends to be the most enjoyable part of wedding planning1.

After drawing circles for all the seats and guests in excalidraw.com, I began connecting the circles with colourful lines to map out specific relationships. As an example, a couple at the wedding should be seated together.

It dawned on me that this is a constraint satisfaction problem (CSP); and modeling CSPs is something I've been doing for the last year.

Constraint Satisfaction Problems

CSPs are a family of problems where you are required to find the value to a number of variables given certain constraints to those variables. There are many areas that such problems occur, one such area is packing optimisations.

There are software engineering roles that rely on solving these type of questions; typically these roles will include the term "Formal Methods" under their list of responsibilities.

To solve a CSP problem, we begin by modelling the problem mathematically. There are a few notations that allow us to define the variables and constraints for these kinds of problems, the one I am familiar with is called SMT-language.

Here is a simple example where we wish to find valid values for x and y:

(declare-const x Int)

(declare-const y Int)

(assert (> x 0))

(assert (< y 10))

(assert (= (+ x y) 15))

(check-sat)

(get-model)

You may have noticed that this uses prefix notation, i.e.

(> x 0) which is equivalent to (x > 0) in the familiar

infix notation.

To find valid solutions we need a solver such as z3.

If we provide z3

with the file above it will give us a solution for x and

y that fits the constraint. E.g x = 15 and y = 0. There

may be more than one valid solution. Sometimes there is not

solution and it will return unsat. Short for

unsatisfiable.

Knapsack problems

We can use z3 and smt to model and solve a classic knapsack problem. Given the following products:

- Product A has a size of 3 and value of 4.

- Product B has a size of 5 and a value of 7.

Pack a bag with a capacity of 16. Maximizing the total value of the bag.

(declare-const productA_count Int)

(declare-const productB_count Int)

(declare-const total_value Int)

(assert (>= productA_count 0))

(assert (>= productB_count 0))

; Product A: size=3, value=4

; Product B: size=5, value=7

; Bag capacity: 16

(assert (<= (+ (* 3 productA_count) (* 5 productB_count)) 16))

(assert (= total_value (+ (* 4 productA_count) (* 7 productB_count))))

(maximize total_value)

(check-sat)

(get-model)

Solving this tells us that if we pack two of each product we maximize the total value of the bag; this being 22.

Seating

Getting back into the seating chart. I wrote (vibed) a program that allowed me to draw different connections between each of my guests. These connections account for the different constraints we wanted to map onto the guests. So if A and B are a couple, ensuring they sit next to each other is a constraint.

Here is a complete list of the constraints that were modeled:

- Sit next to each other.

- Sit opposite each other. Or constraint 1.

- Sit diagonally across from each other. Or constraint 2.

- Not next to, not opposite and not diagonal from each other.

- A should be next to B OR C.

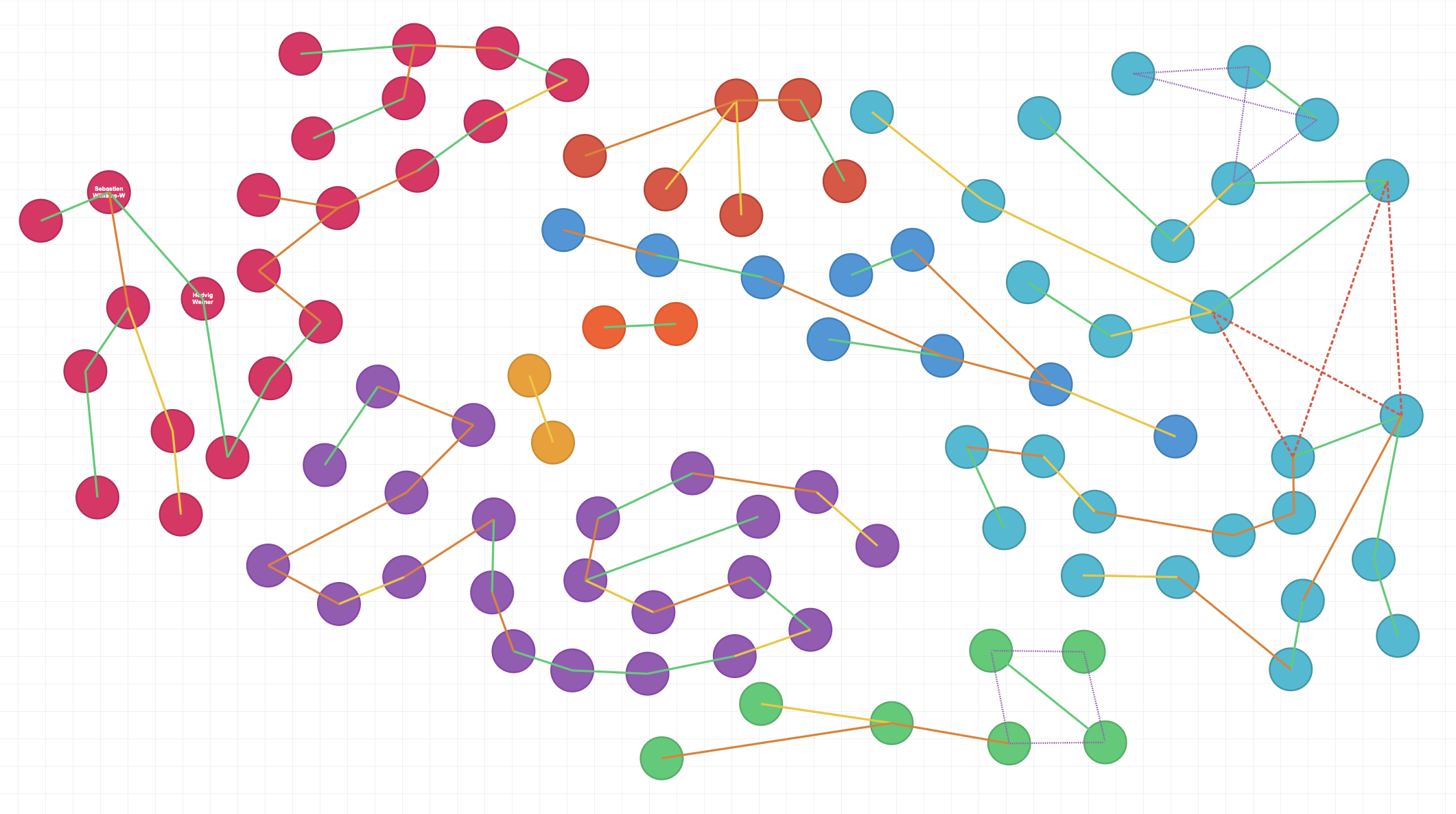

After drawing all these constraints between our guests this is how the wedding looks:

Green is constraint 1, yellow 2, orange 3, dashed red 4 and dashed purple is constraint 5.

We are seating everyone at two large tables. As would have been done in a classic viking longhouse. In order to model the guests at these tables each guest will need a variable for the position, the side and the table.

The groom will have an assigned seat, in the middle of the first table facing inward, towards the guests. As guest number 1 he would have the following variables:

# table_1: int = 0

# pos_1: int = 12

# side_1: bool = true

This would seat me in the middle of the table looking out

across the room. We then define these variables for all 100

guests. We also need to include a constraint that all the

table_{n} variables must be 0 or 1, since there are only

two tables. Additionally the pos_{n} variables have to be

between [0 and 25) since there are only 25 seats on each side

of the tables.

Constraints

Now we model each constraint listed above. The first constraint states that guest A and B must be next to each other. If we take guests 11 and 12 this would look like the following:

(assert (= table_11 table_12))

(assert (= side_11 side_12))

(assert (or (= pos_11 (+ pos_12 1) (= pos_12 (+ pos_11 1)))))

I.e. Same table, same side but their positions are offset by 1 or -1.

The next constraint allows the guest to

not only sit next to someone but as an alternative they can be

opposite each other. To do this we assign the above

constraint to same_side_const and define a new constraint

assign it to opposite_const and in order to satisfy either of

them we say. (assert (or same_side_const opposite_const)).

Here's the definition of opposite_const:

(assert (= table_11 table_12))

(assert (distinct side_11 side_12))

(assert (= pos_11 pos_12))

I.e. Same table, different sides but same position.

For the 3rd constraint we merge constraint 1 and 2 together. B needs to have a different side to A and the position needs to be offset by 1 or -1.

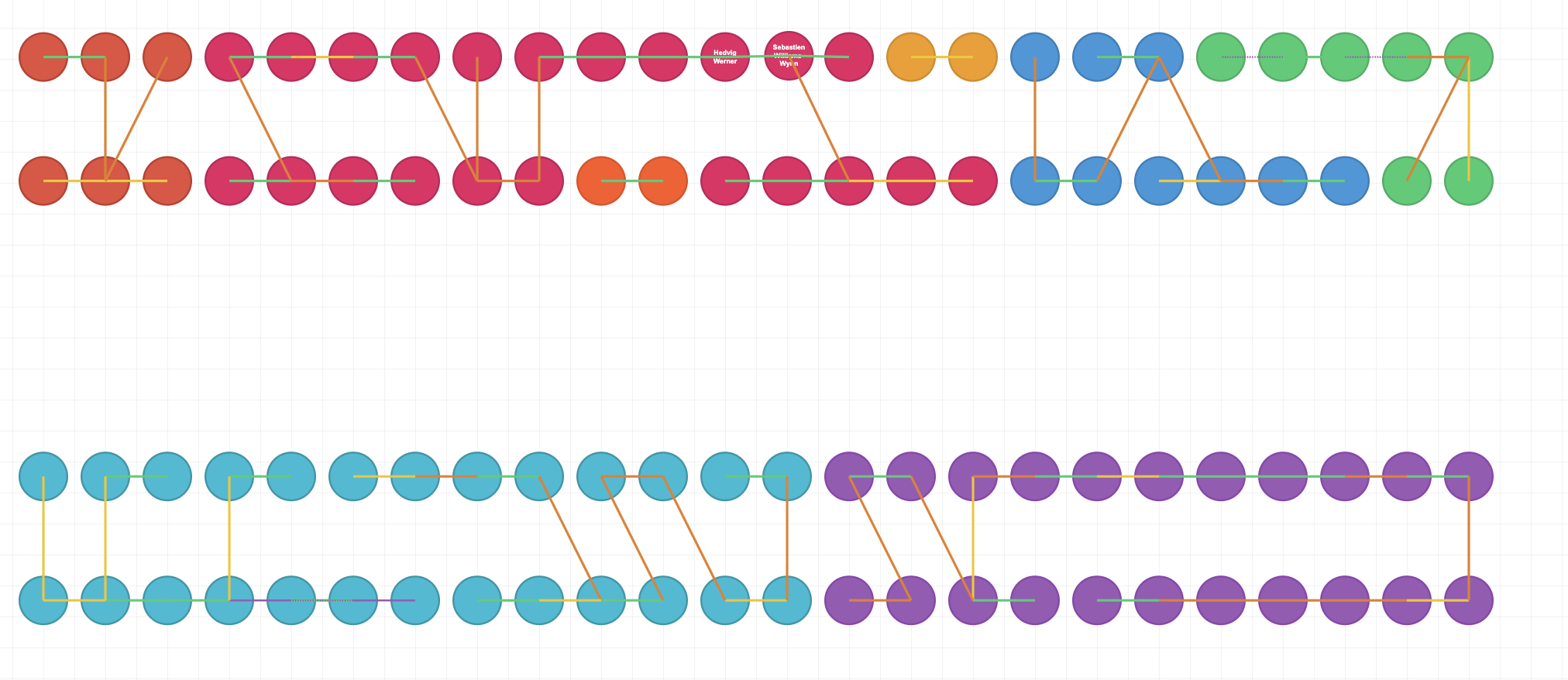

Using the tool above to define the graph constraints I could then export the constraints to be passed into a script that generates the smt file for z3. It then provided a solution that I could import into the same tool to see a visual representation of how it would seat all the guests. You can see that below:

As you'll notice from the colour of each line, all the constraints are satisfied.2

Results

So after 5 hours was this seating chart useful? Not really...

The guests that are on the edge of each of the clusters weren't really people we wanted to sit together. However the arrangement within each cluster was great.

Was this fun? Totally!

I'm not going to do this again, because I'm not going to be married again, but in the event that I have to create a seating chart for 100 people in the future there are certain things that might provide a better outcome.

Perhaps it would be better to rely on more flexible constraints, as an example instead of saying A and B need to be in close vicinity I would instead say A should sit next to at least B, C or D. Giving more flexibility to who A can be sat next to.

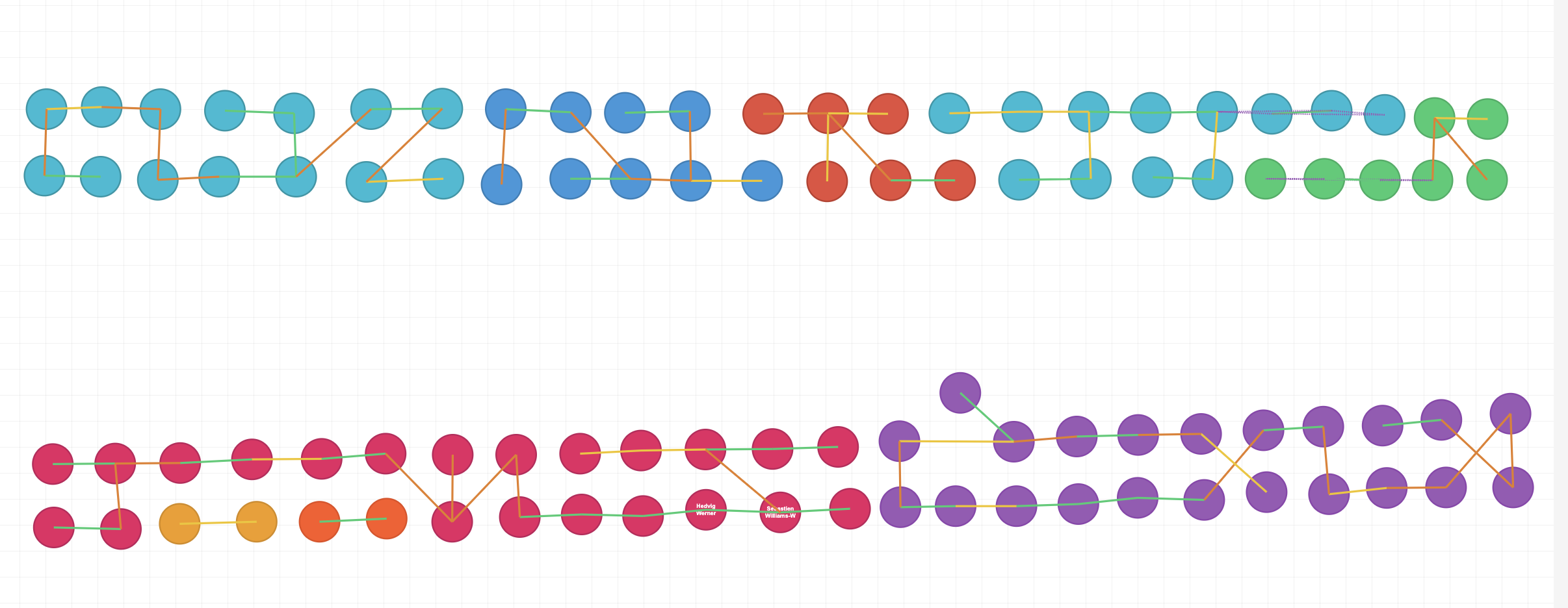

After presenting this analysis to my future wife she showed me how she had laid out the tables. You can see this below.

Since the constraints are already linking the guests, I was able to spot some improvements to the chart and get some value from this effort.

There was another improvement to the modelling I could have made when looking at the final chart.

If we wanted A to sit next to C and A was in a couple with B. I had not considered that it was probably fine for B to sit next to C instead of A. If C would get on with A there's a chance they would also get on with their partner B. So I could have relaxed this constraint and had C sit next to either A or B.

Creating a seating chart is not a recurring problem of mine, so sadly there's no need for me to refine this solution further.

Guests forgetting to tell me that they're coming has also caused me to pull some hair out, as with most math, when it attempts to model the real world.